Project: Twining Cedar- Restoring the Art and Cultural Practice of Tsimshian Bark Basketry

Grantee: Anchorage Museum Association in partnership with the Haayk Foundation

Photos by: Wayde Carroll

[one_half last=”no”]

[/one_half][one_half last=”yes”]

Written by: Kandi McGilton

The Haayk Foundation – a nonprofit organization located in Metlakatla, Alaska, whose primary goal is to save Sm’algyax, the endangered language of the Ts’msyen people, is partnering with the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center, Haida master weaver Delores Churchill, and fluent Sm’algyax speaker and teacher Theresa Lowther to host a traditional Ts’msyen false embroidery basket weaving class for beginning weavers in Metlakatla, Alaska in order to create a digital documentary which will preserve this unique art form as well as the Sm’algyax associated with this indigenous activity.

Delores learned from Ts’msyen weavers like Flora Mather and is the last true master of this unique style. The Ts’msyen of the Annette Islands Reserve were highly influenced by their neighbors the Tlingit and Haida and the beautiful false embroidery on their baskets. Using a different twist combined with the elements of false embroidery, created a distinct style of weaving which differs from that of the Tlingit, Haida and even other Ts’msyen. It is truly an art form specific to the people of Metlakatla, Alaska.

Unlike the arts used for feasts and potlatches that were banned due to a mistaken belief that Christianity must exclude ancient Ts’msyen ceremonies, the basketry survived in Metlakatla because missionary William Duncan, the Metlakatlans’ spiritual leader, allowed the women to continue weaving so he could sell the baskets in his trade shop. When the ladies like Dora Bolton, Lucy Rainman, Flora Mather, and others passed away, there were no young weavers who had learned this style to pass down their knowledge within the community.

With her apprentice and Haayk Foundation board member Kandi McGilton, Delores taught the first phase of the class in the traditional way of harvesting and preparing red cedar bark. They also gathered and prepared maiden’s hair fern and canary grass for the false embroidery designs they will be creating on their baskets. The students were fantastic, quick and eager to learn and there was an air of pride and excitement around the class because through this weaving project, they will help preserve not only the weaving style of their great grandmothers, but also aspects of Tsimshian language that have fallen out of use.

In November as the students come together in the second phase of the class to finish their projects they will also collaborate with fluent Sm’algyax speaker Theresa Lowther. Theresa will narrate the entire process of weaving a basket in Sm’algyax. Theresa’s help in preserving these words is the most crucial part of the entire project because Sm’algyax is a dying language. There are estimated to be 40-60 fluent speakers left in the world, all over the age of 60. In Metlakatla, Alaska, there are only five fluent speakers remaining. The words for traditional Ts’msyen formline have already been lost to time and the Haayk Foundation is committed to preventing Annette Island style basketry from suffering the same fate. At the end of the project, there will be video, photos, diagrams, and written curriculum on how to weave a traditional Ts’msyen False Embroidery Basket in both Sm’algyax and English available for free to the public.

“We are fighting two battles here, to save a dying art unique to the history of our people and a dying language that makes us who and what we are as Ts’msyen people. The Haayk Foundation believes wholeheartedly that the language belongs to all of us and we will do what we can to help it survive for future generations. Partnering with all of these amazing people has been an experience we will never forget and it means more to us than we could ever express.”

[/one_half]

Written by: Annette Topham

In June I had the opportunity to participate in the first half of a two part community workshop made possible through funds from The CIRI Foundation. The opportunity to learn the process of harvesting cedar bark the way our ancestors did from Master Weaver Delores Churchill was an opportunity of a lifetime. Coming together as a community reminded me that our ancestors came together, not only to create functional basketry, but to learn from one another and deepen community relationships. Coming together has done the same for our modern community of weavers. Having this experience is inspiring us to meet together more often, to learn from one another, to share, and to be proactive in teaching a new generation of Tsimshian weavers.

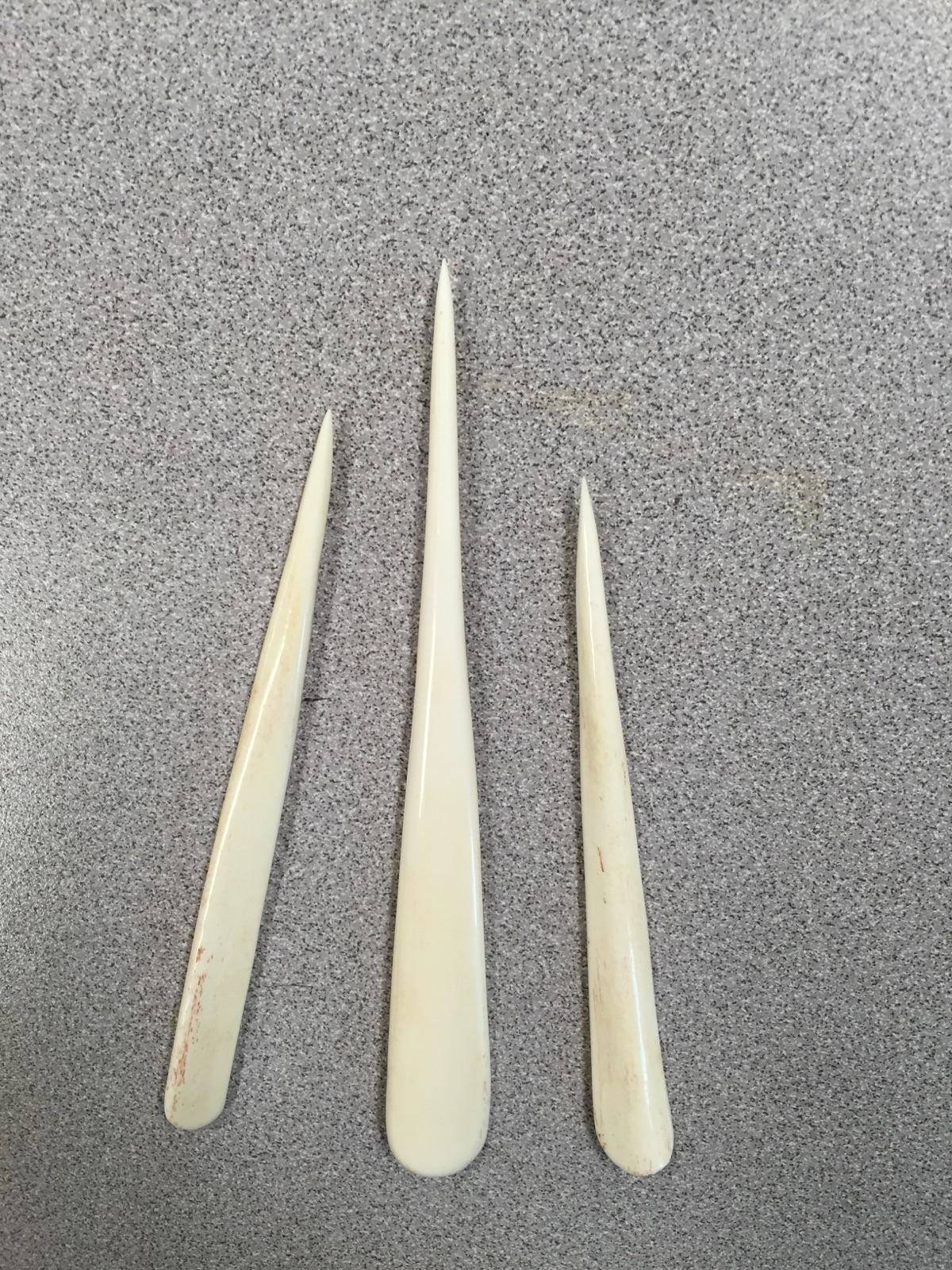

The Experience of Rediscovering an Old Tsimshian Weaving Tool:

It’s day two of “Twining Cedar”, a community workshop held on Annette Island in the Tsimshian village of Metlakatla. We are fortunate to be in the presence of Master Weaver Deloris Churchill. The day prior was spent in the rain forests of Annette Island harvesting cedar bark, an inspiring day of learning for all of us.

Today I’m sitting at a long work table in the Artist’s Village, strips of cedar line the tables. We are processing the bark we harvested the day before. Across from me is Monica Shah, Director of Collections and a Conservator for the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center in Anchorage. Monica is asking me questions about traditional Metlakatla Tsimshian basketry. “I remember Auntie Lillian using a boning tool of sorts to process bark into workable strips. It was used to separate the fibers while allowing the bark to follow the natural grain of the wood,” I explain. This can also be done with a sewing needle and often weavers use their finger nails for the same purpose. Monica is very interested in the bone tool. “ Was it made of real bone?” she asks. I think about this and realize I don’t know. I realize all my memories of this tool are unclear and find myself thinking about it all afternoon. By the end of class that day I am determined to learn everything I can about the bone tool I don’t see anyone using anymore.

I’m staying with my brother John, a Tsimshian Artist and Native Art Teacher at Metlakatla High School. During our lunch break I find John.

“ Do you remember Auntie Lillian’s bone tool?” I ask.

He remembers.

“ Was it a real bone? ” I ask.

It was. He recounts a story of Auntie Lillian describing these tools to him years ago in her later years and he was able to make them for her.

“ They were deer bone… I can make one for you ” he says.

“ What? Yes! Will you make two?”

I want to share this with Monica, it was her line of questioning that ignited my inquiry. I call my father, an avid Tsimshian basket collector who loves to tell stories about helping his mother harvest, process, and weave cedar bark as a child.

“Do you remember your mother’s bone tool? I ask.

My dad is 79, he remembers and spends the next few minutes reminiscing about it. I tell him John is making me one and he is pleased. I can’t wait to have this tool in my hands.

The next morning John goes to school early and returns in time to catch me before I leave for class. “ My entire classroom smells like deer bone now, my students are complaining”.

Then he smiles and hands me a beautifully handcrafted deer bone weaving tool, I almost cry. Goose bumps emerge on my arms accompanied by an indescribable feeling of connection to my ancestors. This is the tool they used. That evening I arrive home to find 3 more beautifully handcrafted, polished deer bone tools waiting for me on John’s kitchen table.

Over the following weeks I spend time with this tool. The way the polished, tapered bone glides almost effortlessly between the layers of bark is unparalleled to any tool I’ve used in the 34 years since learning at the feet of my aunt, and I know this class has been, for so many reasons, a journey to what matters.